Colouring linen, and later wool, red in ancient Egypt seems first to have been done using red ochre. From around 1500 B.C. madder seemed to become increasingly common as a red colourant.

Colouring the dead with the mineral red ochre (iron oxide) was not confined to Egypt but seems a common practice cross-culturally. Use of ochre goes back over 300,000 years and the substance was used by Neanderthals as well as our closer ancestors. In Wales we have the 'Red Lady of Paviland', a male burial found covered with ochre, dating to around 3300 BC.C.. Of course, it could be that past societies also made use of red ochre in everyday life but there is less evidence for it. Today, ochre is still used by some groups of people to adorn the hair and body.

In Ancient Egypt

Ochre occurs naturally in Egypt in the Oases of the Western Desert, and in areas around Aswan.

In burials of the predynastic period, palettes for grinding pigments are found on both burial and settlement sites. Perversely, perhaps, green malachite seems to have been the most common pigment used for burials, while ochre was mainly found on palettes from settlements (Baduel 2008). Fifth millennium graves from Badari contained chunks of red ochre and fourth millennium period graves from Bhutto in lower Egypt were part covered in ochre. A burial at Hierakonpolis dating to 3650-3500 B.C. contained, among other items, junks of black galena used as eye pigment but also chunks of ochre. Another elite burial contained cloth pigmented with iron oxide (Jones 2002).

In the Old Kingdom (2700-2200 B.C.) the use of ochre continued, with red cloth being used for mummy wrappings. Analysis shows red ochre was also used in the 12th Dynasty (c.1800 B.C.) to dye linen (Wouters 1990). It was used, for example on the red mummy wrappings of Khenmit and Ita at Dashur. Iron oxide was also used to dye votive animal mummy wrappings of 3rd century B.C. to the 3rd century AD (Tamburini et al. 2001). [Although I have used the term 'dye', the term 'pigment' may be more apt for mineral colourants. Mineral colourants do not dissolve in water or form molecular bonds with the fabric].

As well as being used to colour linen, the ancient Egyptians also used red ochre to colour paints (for tomb, temple and other painting), as a medicine to help with eye ailments, to paint images on pottery, and to write on papyrus. Coffins and shrouds were frequently coloured red throughout the Dynastic Period.

The use of red continued beyond the New Kingdom, though from around 1500 B.C. madder and tannin frequently replaced iron oxides to colour textiles red, though iron oxide has certainly been found in votive animal mummies of the Roman Period. Use of madder to colour red, may have been introduced from the Levant.

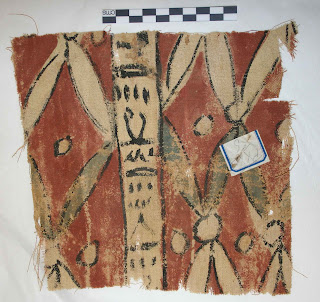

In the New Kingdom, coloured linen seems to have been used by the elite, but here cloth was not only coloured red, but also blue and yellow. For example, Howard Carter found four pieces of coloured cloth from the tomb of Tuthmosis IV (left). Although I say he found them, the actual discovery was made by a dog! Rosalind Janssen (1992, 218) quotes Howard Carter: "I must, however, admit that the original discoverer of the first piece of tapestry-weaving was an inquisitive pariah-puppy, of inborn excavating tendencies. Amid a mass of rubbish were tattered fragments of mummy linen; amongst these the puppy suddenly became active, and after a bout of foraging seized a piece of linen and ran away in triumph with his prize. I pursued him and rescued what I discovered to be a piece of tapestry-woven fabric, which immediately suggested a further search".There were also several dyed linen pieces from the tomb of Tutankhamun, probably dyed with woad and madder. However, the use of ochre continued. A few pieces from Amarna were coloured with iron oxide rather than madder (Kemp and Vogelsang-Eastwood, 2001, 153-154).

Madder used with alum and/or tannin may have been preferred because it was more colour fast when washed repeatedly. However, colouring cloth with minerals can have some advantages. Indeed, minerals are still sometimes used today to colour textiles, for example the famous mud cloth of Africa or the Bengala mud dyes. They can have the advantage of other dyes in being usable cold and, as mordants are not used, they have a low environmental impact. Iron oxides are colour fast and while they can be washed out of fabrics, it is not easily done. It is possible too that some sort of glue, such as milk, was used to help the mineral stick to the cloth. However, mineral pigments can cause textiles to decay. In the case of linen, however, such decay appears slow, with wool it is quicker. The later use of wool may have accelerated the preference for madder of ochre as a textile colourant.

EC116, from the Egypt Centre, is just one of thousands of (madder) red-dyed shrouds of the Roman Period in museums across the world. It is part of the long Egyptian tradition of dyeing funerary cloth red.

Red was the colour of the sun-god Re and rebirth, it was associated with dangerous beings but was also associated with life and with protection. Red cloth was given as a daily offering to the gods. Indeed, as late the fourth to seventh centuries AD, Egyptian linen textiles sometimes included seemingly stray red threads, almost hidden, which Rooijakkers (2017) has seen as protective.

References

Baduel, N. 2008. Tegumentary paint and cosmetic palettes in Predynastic Egypt: Impact of those artefacts on the birth of the monarchy. In Egypt at its origins 2: Proceedings of the international conference "Origin of the State, Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt," Toulouse (France), 5th - 8th September 2005, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 172. Eds. Béatrix Midant-Reynes, and Yann Tristant, pp. 1057-1090.

Janssen, 1992. The Ceremonial Garments of Tuthmosis III Reconsidered. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur, 19 (1992), pp. 217-224.

Jones, J. 2002. Funeral Textiles of the Rich and Poor. Nekhen News, 14, p13.

Kemp, B.J. and Vogelsang-Eastwood, G. 2001. The Ancient Textile Industry at Amarna. The Egypt Exploration Society.

Rooijakkers, T. 2017. Tracing the Red Thread. In Excavating, Analysing, Reconstructing: Textiles of the First Millennium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries. Proceedings of the 9th conference of the research group 'Textiles from the Nile Valley', Antwerp, 27-29 November 2015. Eds. de Moor, A, Fluck, C. and Linscheid, P. Lanoon, pp. 242-251.

Tamburini, D, Dyer, J., Vandenbeusch, M. et al. 2021. A multi-scalar investigation of the colouring materials used in textile wrappings of Egyptian votive animal mummies, Heritage Science https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00585-2.

Wouters, J. 1990. The Identification of Haematite as a Red Colorant on an Egyptian Textile from the Second Millenium B.C. Studies in Conservation, 35, pp. 89-92.